- Home

- Robert Matzen

Fireball

Fireball Read online

Fireball

Carole Lombard and the Mystery of Flight 3

Robert Matzen

GoodKnight Books

www.GoodKnightBooks.com

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

For the one who, when I said, “I need to climb one of the roughest mountains in the United States,” responded without a second’s hesitation, “Me too. When do we go?”

Contents

Acknowledgments

Prologue: All Uphill

1. A Perfectly Routine Friday Night

2. Perpetual Motion Machine

3. The Radiating Halo

4. The Long Road

5. A Long and Grim Weekend

6. Merely Physical

7. A Perfect Flying Experience

8. Inflexible Fate

9. Jimmy Donnally Lands His Plane

10. Calculated Mayhem

11. Flight 3 Is Down

12. A Man in a Man's Body

13. The Plane That Fell

14. Somber Hymns and Cold Marble

15. Hoping Against Hope

16. Certified Bombs

17. The Plain, Black Night

18. Malaise

19. Road King

20. A Flame to Many Moths

21. Fool's Errand

22. The VIPs

23. Gleaming Silver

24. The Coin Flip

25. The Computer

26. Stranded

27. The Glamorous Life

28. I Won't Be Coming Home

29. There's No Rush

30. Caring Enough to Climb a Mountain

31. The Entire Gang Showed Up

32. Groaning Pines

33. Unfixable

34. I Still See It in My Dreams

35. The Fatal Flaw

36. The Complication

37. Just a Few Yards Apart

38. All in a Day’s Work

39. The Little Boy Was Gone

40. Flying with Full Acceptance

41. The Under Side

42. Even the Unfortunates

43. The Cream of the Crop

44. Skyrocketing

45. Mangled

46. If I Can Do It, So Can You

Epilogue: High-Energy Impact

Fireball: The Story in Pictures

Chapter Notes

Selected Bibliography

About Robert Matzen

Copyright

Acknowledgments

The development of this book was pure magic, from long before the climb of the mountain. I would like to thank John McElwee for sitting with me in Columbus, Ohio, and laying out a vision for the book that became Fireball, and Carole Sampeck for her expertise and especially for her sensitivity, partnership, and gentle spirit in fulfilling the Fireball vision. It couldn’t have happened without you, CB.

Many others were essential to this project and their contributions unique and invaluable: Mary Savoie spent time telling me what it was like to ride on Flight 3 for 1,500 miles the day it crashed, Tom Wilson put me on the trail of Mary Johnson, Marie Earp connected me with the Savoie family, and Spencer and Becky Savoie told me about the incredible Mary and shared a hoard of fascinating information about her role in the last cross-country trip of TWA Flight 3; Jim Boone provided intrepid leadership in the climb of Potosi Mountain; researcher Ann Trevor unearthed great treasures, including the TWA crash files and the House transcripts; Marina Gray made many incredible research finds on the people aboard Flight 3 and helped to secure the Myron Davis photographs; David Phillips (a great guy) made it possible to land the photos of Myron Davis for this book; Steve Hayes gave his time and extra effort to reminisce about his friends, Clark Gable, Lana Turner, Ava Gardner, Franchot Tone, and Robert Taylor; Lyn Tornabene donated her research materials to the Academy and thus made them available to me for this book; Marie Levi and Donita Dixon shared information about their cousin, Lois Mary Miller Hamilton; Burton Brooks helped to connect me with Doris Brieser, who reminisced with me about Aunt Alice (Getz), and she and Cindi Lightle shared their amazing family scrapbook; Steve and Doug Van Gordon provided photos and information about their father, Lyle, and mother, Elizabeth; Nancy Myer gave insights on Lombard and Gable; Stacey Behlmer and the staff at the Margaret Herrick Library at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences generously and patiently helped Mary and me comb the archives with emphasis on the Lyn Tornabene collection; Mike McComb made available the CAB transcripts and key photos, and lent his aviation and research expertise to the project; David Stenn provided guidance, leads, and research on both Gable and Lombard; Nazoma Roznos Ball spent hours on the phone with me talking about Jill and Otto Winkler and made available Jill’s original manuscript detailing the events leading up to the bond tour and the night of the crash; Mike Mazzone lent his expertise on John Barrymore and the production of Twentieth Century; Fred Peters III spoke with me about his father, Fred Peters, Carole Lombard’s brother; Robert and Rosemarie Stack and their dog, Hollywood, shared their home with me on a memorable day as Bob reminisced about Carole; Debra Sloan-Shiflett went with me that day and helped with research on Lombard; Sharon Berk created another terrific book design; David Boutros and the University of Missouri-Kansas City conserved and made available the TWA files pertaining to the crash of Flight 3; Scott Eyman discussed with me the concept of Fireball and lent his expertise on both MGM and Ernst Lubitsch; James V. D’Arc shared his knowledge, energy, and enthusiasm about the project; Jeff Mantor, Mike Hawks, and the Larry Edmunds Bookshop provided friendship and support; Richard Roberts supplied his notes from interviews with stunt pilot Don Hackett; Neve Rendell lent perspective on Clark Gable; Jack El-Hai graciously granted permission to use portions of his blog about the Lombard FBI file; Robb Hill gave advice on climbing to the crash site and Las Vegas Review Journal news articles pertaining to the crash; Bob and Kathy Basl worked their magic to recapture the splendor in camera negatives created by Myron Davis; and Val Sloan provided her usual photo cleanup wizardry. Lastly, I would like to thank Mary Matzen for taking on Potosi, walking up to the Encino Ranch, sitting with me at the Lombard and Gable crypts, researching at the Academy, reading this thing not twice but three times, and in all ways helping to make Fireball the book it needed to be.

Prologue: All Uphill

The book that became Fireball began with a mention of the fact that much of the wreckage of TWA Flight 3, a commercial airliner carrying Hollywood star Carole Lombard and 21 other people on the evening of January 16, 1942, still today lay strewn across the side of Mt. Potosi, Nevada. I said this to my friend and colleague John McElwee, author of Showmen, Sell It Hot! and host of the Greenbriar Picture Shows website. Most people don’t know that the engines, landing gear, and various twisted chunks of fuselage remain entangled in brush, rest against trees, and, in general, litter the surface of some of America’s most inhospitable real estate within sight of Las Vegas, Nevada.

Some months after our conversation, John suggested lunch with my wife, Mary, and me at a film convention in Columbus, Ohio, because he wanted to hit me with an idea, an inspiration for a book. This book would juxtapose a modern-day climb of the mountain to that remote crash site with the events of 1942, Carole Lombard’s last days, her decisions on the trip from Indianapolis, Indiana where she went to sell war bonds, and husband Clark Gable’s reaction to the loss of his wife. John and I both knew that the story dripped irony and that such a book would be what he called “dynamite.” Then he jabbed a finger in my direction and said, “And you are the only one to do it.”

Mt. Potosi (an Indian word pronounced POE-tuh-see) rises to an elevation of 8,200 feet above sea level and looms over the desert west of Vegas. There are no roads to the crash site and no trails. Nothing much lives up there because even a mountain goat would

have better sense than to scale grades so steep.

It took some months to get the climb organized, equipment rented, and guide secured. Mary and I set out to climb Potosi toward the end of October when the desert would be cool and the snakes charmed. By that time I itched to write the story that had been laid out, but I knew I must make the climb before I could feel any entitlement to set down a word of this book, and I had to accomplish this feat over the route that first responders took, and Clark Gable tried to take, when all still believed that survivors might be found up on the mountain.

A local conservationist named Jim Boone guided us that day. We started out in a four-wheel drive Jeep with hubs locked, and after an hour bouncing along old mining roads, we unfolded ourselves from the Jeep on scrambled legs and began our hike that turned into a climb; a dangerous passage that left me bloodied before the first mile had passed.

Mary, who is plenty tough, surrendered halfway up, and Jim led me on, climbing with annoying ease while I grunted and clawed behind him. It took four-and-a-half hours all told to ascend the mountain on foot and after all the climbing, stumbling, and bleeding, I wasn’t prepared for the experience of being at the spot of the crash. A fair amount of DC-3 number NC 1946 does indeed remain scattered over the side of the steep mountain slope, so much so that every footfall caused a tinkle of aluminum in shards and chunks. It’s a place where 22 people departed this earth in one flaming second, and that hit me very hard.

When Jim found a bone that had been part of somebody’s hand, I understood that this wasn’t just Carole Lombard’s story. It was the pilot’s story and the co-pilot’s and the stewardess’s. It was the story of 15 Army Air Corps personnel who perished, men as young as 19 and as “old” as 28, and it was the story of three other civilians, all of whom died right there, on the spot where I stood shivering in the fading October sunshine at 7,700 feet.

I started writing on the plane ride home and haven’t stopped since. I have had extreme good fortune in my research, accessing the complete Civil Aeronautics Board investigation, including the exhibits and testimony. I have examined the U.S. House of Representatives investigation, and TWA’s complete, never-before-seen crash files. I found a passenger who flew across the United States with Carole Lombard on Flight 3 and left the plane before it crashed. And I have learned of some of the contents of the FBI files. I spoke to a number of relatives of Flight 3 crash victims, pored over hundreds of newspaper accounts and unpublished manuscripts, and sifted through raw research data, including previously unpublished interviews about Carole Lombard and Clark Gable.

With the assistance of Lombard/Gable expert Carole Sampeck and many others, I have been able to debunk some legends and verify others, and make some conclusions about the people and events. The result is equal parts biography, rescue effort, and mystery; it’s also a love story and an unimaginable tragedy that continues to haunt me, as it may haunt you.

Robert Matzen

August 2013

Pittsburgh, PA

1. A Perfectly Routine Friday Night

It was after 6:00 P.M. on the evening of January 16, 1942, when Private First Class Tom Parnell first learned that a TWA airliner intended to stop at McCarran Field in Las Vegas. Pfc. Parnell worked the tower of the Army airfield that evening, and it was going to be a cold one, temperature down around 40. McCarran had been leased to Transcontinental and Western Airlines or TWA and Western Air Express for use as a commercial field, which meant that the place saw more action than if it had been occupied by the Army alone. Parnell hadn’t been expecting to work this evening, but a buddy, Private Craft, had asked him to switch so he could go to the pictures, and Tom said yes because maybe he would need a favor himself down the line.

Now, at 6:26, Parnell received a radio call from TWA Trip Number 3 inbound from Albuquerque asking for wind speed and a runway assignment. Parnell had been handling these duties for only a week and knew he needed some practice with his radio calls. He hoped his inexperience couldn’t be heard as he radioed, “Winds are calm from the east. No traffic at this time. Captain’s choice of runway.” McCarran Field had two landing strips, a north-south runway and a diagonal northeast-southwest runway.

Three minutes later Parnell spotted the twin beams of forward landing lights on a DC-3 as it swung to come in from the southwest, and TWA Flight 3 eased into a smooth landing. It was a new DC-3 with a polished aluminum body. A black TWA emblem showed on the left wing surface, and the plane number NC 1946 appeared atop the right wing. In red script above the eight rectangular passenger windows along the fuselage read the words, Victory is in the air—BUY BONDS.

With the plane safely landed and taxied to the station, Parnell stood down on an otherwise quiet evening. He knew nothing about the plane and didn’t much care. With a glance he noticed Army guys piling out, which was usual these days with the war on. Parnell cared only that the plane had landed safely, and once he saw that it took off safely in a few minutes, his job would be done.

On the runway 31-year-old TWA station manager Charles Duffy walked from the station into the cold night air. He pushed aluminum steps on wheels out to the cabin door of the plane. The door swung open and there stood the air hostess, a good-looking brunette with dark eyes. Duffy moved the steps into place, locked the wheels, and climbed up to receive from the hostess a card that contained cargo and passenger information. She smiled as she handed it down and made eye contact that could have been flirtatious; he didn’t know.

Duffy moved down next to the stairway and watched a number of Army men step off the plane, one set of striped, olive-drab pants after another. It was his habit to make sure each passenger descended the steps smoothly without mishap, so he watched legs and feet. Legs and feet. Suddenly a very different leg appeared; a shapely leg in stockings and heels. He held out his hand instinctively to help a lady off the plane and looked up into the face of a pretty young woman with black hair. She smiled, thanked him, and moved past. More Army men stepped down. Bang. Bang. Bang. Precise masculine strides, one after another.

Then another toned leg appeared beneath another hemline. Duffy caught the glint of an ankle bracelet, and saw a black high-heeled shoe. He held out his hand again. A gloved hand took his, and when he looked up he was staring into the sculpted face and topaz-blue eyes of motion picture actress Carole Lombard. No mistaking it; she was a distinctive-looking woman. Duffy attempted to hide the fact that his heart had skipped a couple beats—to show that he was startled would be seen as unprofessional. The movie star managed a faint smile, forced it he thought, as she stepped off Flight 3 into the cold desert night. It was funny how the brain worked. In the split second that he had made eye contact with this woman he had never met, he could tell she was exhausted. Her makeup had worn off hours earlier revealing pale skin and circles under the eyes the color of storm clouds. Two other passengers seemed to be with her, a middle-aged man and a much older woman, and all proceeded into the station to stretch their legs and warm up while the plane refueled. Notables routinely appeared at the little Las Vegas airfield because of its proximity to the bigger air terminals at Burbank and Los Angeles to the south and west. Just 90 minutes of airspace separated Las Vegas from the movie capital of the world.

Flight 3’s block time was 6:36, and Duffy followed the last of the passengers, one more cluster of soldiers, into the station. His was a high-pressure job, handling all the paperwork and cargo for the flights en route as well as passenger questions and final clearance with TWA control in Burbank. He heard the fuel truck being driven into place and knew that things were moving smoothly. Trip Number 3 was a transcontinental flight that had begun at LaGuardia in New York City the previous day, then stopped at Pittsburgh, Columbus, Dayton, Indianapolis, St. Louis, Kansas City, Wichita, Amarillo, and Albuquerque. The flight crew would have changed over a couple times by now, along with all the passengers, so the DC-3 itself and some of its cargo and mail contents were the only constants from New York City all the way to lonely Las Vegas.

&n

bsp; Out at the plane, young Floyd Munson, not yet 18, leaned a ladder against the fuselage, and Ed Fuqua, the cargo man, climbed up on the wing and sticked the fuel tanks. He scribbled numbers on a slip of paper and handed it down to Munson, who walked the paper inside and stuck it in Duffy’s palm before ambling back to his duties at the plane.

As Chuck Duffy processed paperwork, some of the Army personnel from the plane stood in a group, smoking and talking. Others sat quietly, one of them already slumped asleep in a chair. They were various ages, up to 30 he thought, but mostly they were young, barely shaving, and full of enthusiasm. Carole Lombard shared none of their energy or good spirits. All the while, she paced in front of the two other people, the businessman with slicked-back hair and the elderly lady who had followed the actress off the plane. Duffy glanced at the passenger list. Otto Winkler was the only civilian male he saw on the list, and there were two women passengers, a Mrs. Elizabeth Peters and a Mrs. Lois Hamilton. He wasn’t sure who was who, but nobody looked happy. The actress was pale and thin and wore a sour expression, not at all what he might expect from a star of comedy pictures. The elderly woman sat rigidly in her seat and stared at nothing. Nobody said a word. After a while the businessman approached Duffy and asked to send a telegram. Duffy handed him a Western Union form, and the man scribbled some lines and handed the form back along with a quarter.

Out the corner of his eye Duffy saw the pilot edge up to his desk. “Say, is Flight 3 going on to Long Beach?” the pilot asked. Duffy replied that he didn’t have that information and the captain would have to check upon landing at Burbank. Wayne Williams was the captain’s name, one of the veteran TWA pilots but a recent addition to this route, about 40 years of age and a nice guy.

The captain nodded and motioned toward the plane. “Fill the oil tanks to 20 gallons each, will you?” Duffy said he would see it done. He told Capt. Williams that his man had sticked the tanks and there were 125 gallons of fuel remaining on the plane at landing. Chuck said he had ordered 225 gallons to be added for a total of 350. Capacity was more than 800, but Duffy was concerned about weight because he could see from the hostess card that the plane was already maxed out on passengers and cargo. Williams nodded his approval of the addition of fuel.

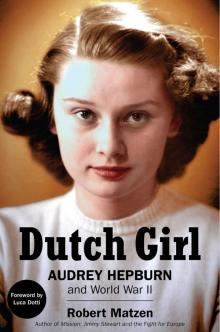

Dutch Girl

Dutch Girl Fireball

Fireball