- Home

- Robert Matzen

Dutch Girl Page 14

Dutch Girl Read online

Page 14

Following the attacks on Arnhem and Nijmegen on 24 February and again the next day, Dutch skies bulged with American bombers aimed at the city of Gotha in central Germany. What went on in the skies over Velp on these two days was like nothing the citizenry had ever seen. Four miles straight up, a deadly dance played out as German fighters faced hundreds of American heavy bombers and their fighter escorts. The skies blazed fire and smoke as the big German flak guns, those that survived the attacks to destroy them, thumped over and over and their shells exploded among the bomber formations. Then, as soon as the cannon fell silent, German fighters swooped in by the dozens and aerial combat raged. Planes exploded or tumbled from the sky in flames. Parachutes brought survivors to earth, and the Germans rushed in to offer aid to their own pilots and capture the enemy as they hit the ground.

But some Allied fliers were helped to evade capture by members of the Resistance, which had a strong presence in Velp located right under the noses of the Nazis. With so many powerful representatives of the Reich gathered in the village, the local Resistance grew just as fervent, and Velp’s hospital, het Ziekenhuis, became de facto Resistance headquarters. The two-story, eighty-bed facility sat on Tramstraat, just three blocks from the Beukenhof—which for the van Heemstras involved a five-minute walk directly past Seyss-Inquart’s villa.

“The mafia had nothing on the doctors of Velp,” kidded Ben van Griethuysen, whose father, Bernhard, served as a radiologist at the Ziekenhuis and also worked at St. Elisabeth’s Hospital in Arnhem. “They all knew each other very well and kept each other’s secrets.” And those secrets on behalf of the Resistance were legion. Dr. Willem Portheine was hiding a small Jewish boy and shuttling other Jews to and from his home, as did Dr. Vince Haag.

Elly Röder-Op te Winkel, daughter of Dr. Wim Op te Winkel, said, “In our home [at Hoofdstraat 7A] were about thirteen Jews and other onderduikers hiding for a shorter or longer period. And our neighbors were members of the SS and SD!”

In fact, all the doctors on staff at the Ziekenhuis were aiding Velp’s sizable onderduiker population. “All doctors hid Jews in their homes,” said Velpsche historian Gety Hengeveld-de Jong. “The Jews—from Amsterdam, Rotterdam, etc.—were brought by the Resistance to het Ziekenhuis Velp and from there the doctors took them in their cars to their own homes and later to different families in Velp.”

Dr. Adriaan van der Willigen Jr., served as chief of staff at the hospital and also a key member of the Resistance. Perhaps the most energetic of the physicians working for the Resistance in Velp was thirty-nine-year-old Dr. Hendrik Visser ’t Hooft, who lived in the shadow of the hospital with his wife, Wilhelmine, and four children in a beautiful early nineteenth century villa called de Leeuwenhoek. The doctor had been a silver-medalist field hockey player for the Netherlands at the 1928 Amsterdam Summer Olympic Games and now used his extensive network of connections reaching out through Gelderland in service of the local Resistance movement.

“He was a charming and good-looking person, a sportsman, hockey, skating, etc., and he was a reliable doctor,” said one of his former patients, Rosemarie Kamphuisen. “As children we loved him and called him ‘Uncle Doctor.’ When we were ill, even with a high fever, we looked forward to his visits and made drawings for him.”

Among his myriad duties, which spanned the length and breadth of Velp, Dr. Visser ’t Hooft served as de huisarts van de Pallandts—visiting doctor to Baron van Pallandt, his wife, and their adult children at Castle Rozendaal. With their kin and frequent guests the van Heemstras so close by, it was natural that connections would be made between the baron, Meisje, Ella, Audrey, and Dr. Visser ’t Hooft.

By this point in the war, the young doctor worked every waking moment. He practiced at an office in his home as well as at the hospital. He also made house calls and his wife, Wilhelmine, helped him keep track of appointments. But she also helped him with a variety of other tasks, some of them menial. Wilhelmine’s responsibilities also included four children as well as family and patients who shuttled into and out of their home on a regular basis—every time the doctor offered shelter to someone displaced or in trouble. Both the Visser ’t Hoofts needed another set of arms and legs in his practice. Given the situation, he asked one of the few people in Velp possessing the vitality to keep up with him, Audrey, for some assistance.

The offer by a key Resistance man in the village demonstrated just how much Ella’s sympathies had changed during the course of the war. Dr. Visser ’t Hooft likely would have used his contacts to research the van Heemstras, and the intelligence must have come back favorable. At the beginning, Audrey’s role meant only handling the most menial assignments, which would free up the doctor to better serve his many patients. She had her career to think about after all, as her training continued at the Dansschool under the tutelage of Marova.

Audrey turned fifteen on 4 May 1944 and faced pressure to register as a member of the Dans Kultuurkamer with its deep ties to the Reich. “You had to be a member of that Chamber in order to study,” said Audrey. “A good Dutchman simply was not.”

Ella and Audrey together faced the inevitability that, for the moment at least, she must give up dance because she must not obtain a Kultuurkamer card. Ella could reason with her daughter that the war couldn’t last much longer, and once it ended Audrey could resume her training with Marova. Ella knew it was past time for both mother and daughter to sever their ties to the Arnhem cultural scene. Louis Lieftinck, director of the employment office in Arnhem and a member of the NSB, had been appointed as an honorary member of the board of directors of the Muziekschool. There was nothing honorary about the appointment, and with this move the Nazi grip on the arts in Arnhem became complete. Rather than sit at a table with an NSBer, the entire board resigned in protest, Ella included, and her final tie to Arnhem, which she had kept in support of Audrey’s career, was severed.

It seemed, according to the BBC and Radio Oranje, that the Germans would be out of power any time now and that Allied victory was inevitable—if, said Queen Wilhelmina, every freedom-loving Dutch man and woman continued to fight. And, true enough, the bombers kept flying over, and kept on, and kept on. Almost every day, hundreds passed by at a time. At night, similar RAF bomber formations made a ghostly noise to break the silence of the late hours.

“As we heard the allied bombers roaring overhead every night bound for Berlin,” said Audrey, “I could not help but think of my brother…though of course I knew the bombers were bringing the end of the war nearer.” Ella and Audrey had heard nothing from Ian other than a message that he was in or near Berlin working at a munitions factory.

The question on everyone’s lips remained: When will the Allies invade northern Europe? The Allied landings in Italy had come to nothing, and they were stalemated on “the boot.” The occupation of the Netherlands couldn’t possibly be broken without an invasion in France because, despite the bombing campaign and devastation of German civilian centers, manufacturing in the Reich had continued, and more tanks and planes than ever were rolling off the assembly lines. Allied bombing had only stiffened the resolve of the Germans, just as had happened for the population of London and, for that matter, for the Dutch after Rotterdam.

Yes, the war dragged on. Day by endless day the nutritional needs of the fighting men of the German war machine were ravaging the civilian population of the Netherlands. Too many vital nutrients had been extracted from the food supply and diverted to German forces; the store shelves had become too empty; animal proteins were nowhere to be found; and a dancer’s muscles could endure it no longer.

The usual description of Audrey at this time: She was “tall and skinny, with big hands and feet.” Said Marova of her star pupil, “She didn’t get the right nutrition, and she fell apart. I agreed with her mother that she should stop dancing temporarily.” It was just as well because she couldn’t perform publicly anyway unless she agreed to join the Kultuurkamer. True enough, Audrey could keep dancing in Velp at the studio of Johnny van

Rosmalen just down the street from the Beukenhof, but there was no substitute for the brilliance of Marova and the resources of the Muziekschool.

With time on her hands, Audrey began giving public dance lessons to local children in Velp at the Netherlands Hervormd Vereniging, or N.H.V., a church building on Stationsstraat that also served as the local civic auditorium. “I wanted to start dancing again,” she said, “so the village carpenter put up a barre in one of the rooms. It had a marble floor. I gave classes for all ages, and I accepted what was about a dime a lesson. We worked to a gramophone wound by hand.”

One of her former pupils described Audrey as “very serious for her age, and she really tried to make something out of the lessons.”

Annemarth Visser ’t Hooft became one of Audrey’s students at age eight, and said, “There are two ways to teach ballet. One is doing all the pliés and classical movements, and the other is, when it’s ballet with children, looking at their way of movement, taking that up, and making a ballet out of it. She was good in that, but she also introduced the basic steps.”

Audrey would say with pride in the 1950s that, “Some of the pupils still correspond, and they always say they don’t know what they would have done without the school. Everyone was made to keep his mind off things. You have to remember that there were no parties, no radios, no new books. I don’t suppose it taught me much as a dancer, but it taught me a great deal about people and work.”

She also booked some more expensive private lessons for the children of prominent families, including Hesje van Hall, who lived in Het Witte Huis on Biesdelselaan in Velp. Hesje’s older brother Willem certainly noticed Audrey, who had just turned fifteen. “I was beginning adolescence and sometimes opened the door and took her coat,” he said. “Audrey had a very interesting look back then. When she came in, the house suddenly seemed completely different. She was very slender and walked so gracefully.” This way that she could cross a room as if gliding, with the gait unique to ballerinas, had drawn the attention of Edouard Scheidius, a young Arnhem attorney and friend of Marova. His nickname for Audrey was Poezepas, or cat-walk.

Audrey devoted part of her week to volunteer work for Dr. Visser ’t Hooft and also provided dance lessons as May, a beautiful month in the Netherlands, gave way to June. Then, on the morning of 6 June, the BBC broadcast an urgent bulletin that ended a year of expectation among the oppressed and the occupiers: The Allied invasion of Fortress Europe had begun! The beaches of France had been stormed at Normandy by the largest fleet of sailing vessels ever assembled! Thousands of Allied troops from a multinational force were trying to establish a foothold and facing fierce resistance!

The day passed with agonizing slowness across the Netherlands. By nightfall it could be reported that the boots of the liberators held firm in northern Europe. Men and supplies of the liberation army began flowing into France, and the Germans rushed troops west to beat back the Allied attack in desperate combat that sprawled across the French countryside.

In the ensuing weeks, thousands of Allied soldiers died in an attempt to move inland. During the long back-and-forth series of battles for France, word came that Hitler’s own generals had tried to kill him at the Wolf’s Lair in East Prussia on 20 July and that he had barely survived the attempt. Supporters of the House of Oranje—ninety percent of the Dutch population—rejoiced at this new sign that the Reich was finally showing signs that it might crumble.

In August after a long stalemate, Allied armies under Patton and Montgomery punched through the German lines and began gobbling up great parcels of French territory. An entire German army was cut off and captured at the Falaise Gap south of the city of Caen.

It seemed to the people of the Netherlands that everything was going remarkably well, and Ella wasn’t wrong: The war might soon be over. Little did anyone at the Beukenhof know just how incorrect she was; the people of Arnhem and Velp were about to learn the cruelest possible lessons about the art of war. Quite simply, their world was about to explode.

16

Black Evenings

“Food started getting scarcer and scarcer and scarcer,” said Audrey. “We ran out of everything. Holland had no imports or exports. It was just a closed country. And, of course, the German army took the best of everything.”

Expectation hung in the air of Gelderland in August 1944. Some units of the German army that had been mauled in the Soviet Union were transferred to the new western front to fight the American and British armies pouring into the heartland of France from the Normandy beaches in the north. Activities by the Dutch Resistance picked up as Oranje Dutch—those loyal to the royal family—began to entertain the idea that one of these days, their country would be liberated. Why not help the situation along where possible?

Through the summer, Audrey’s work for Dr. Visser ’t Hooft, including tours of duty in the Ziekenhuis working directly under the head nurse, Sister van Zwol, brought the Dutch teenager closer to the web of Resistance activities by necessity—the Velpsche doctors working inside the hospital were key to many anti-German efforts, from forging identity documents to facilitating the movement of onderduikers. The hospital became the obvious center for their activities. It was the place where they could talk in safety, and where their imaging equipment—key to document forging—was located.

“The Velp Hospital … was a very important central institution,” said Velp resident Rosemarie Kamphuisen, “not only for the inhabitants [of the village], but also for the doctors who met each other after their visits practically every day.”

These physicians were members of the Landelijke Organisatie Voor Hulp Aan Onderduikers, the L.O., one of four Resistance groups active in the Netherlands by the summer of 1944. At this point in the war, all the Jews in Velp had been “dealt with,” all but those who had gone into hiding. The great number of onderduikers hidden across the village, about 600 Jews plus many others like Audrey’s brother Alex who were hiding for different reasons, served as evidence of the sophistication of the L.O. enterprise supervised by Dr. Visser ’t Hooft and his colleagues.

The doctor for whom Audrey volunteered was quite a swashbuckling character. Earlier in the war, the car he kept hidden in the village had been “betrayed”—an informant had told the Germans about it, leading to confiscation. Somehow he managed to obtain a German motorcycle for transportation, possibly from the black market—a doctor on foot in an area serving several thousand people wouldn’t be effective. One day his ten-year-old daughter Clan stood in front of their house as her father returned home. “He came into the driveway, and I was standing there,” she recalled. “And he put this running motorcycle in my hands and ran off. And I thought, ‘What’s going on?’ A few seconds later, a German patrol came into the driveway to arrest him. And he was gone. And I stood there with this running motorcycle. I didn’t know what to do with it.”

Her enterprising father had earlier cut an escape hole in the iron fence around the family property for just such an occasion, and within minutes of his encounter with Clan, he had hopped a train out of town. He was confident that the Germans wouldn’t harm a ten year old; they would have been satisfied with the confiscation of a motorcycle that a Dutchman had no business possessing. The simple fact was, the Germans walked a fine line with the physicians of Velp—every doctor in wartime was a vital resource, so gazes were averted from some basic transgressions by Visser ’t Hooft, like motorcycle stealing.

Ironically, not long after this incident, the doctor was summoned to the villa on Parkstraat of none other than Seyss-Inquart, who was suffering some ailment. A key member of the Resistance in Velp now faced the moral dilemma of treating his bitter enemy, knowing that if he didn’t, his family might suffer. He also had to wonder if he might be walking into a trap. What did he decide to do? “He went,” said Clan with a shrug. And it wasn’t a trap.

Biographers and many Dutch who lived through the war have doubted the participation of a young Audrey Hepburn in work for the Resistance, saying, “She w

as just a girl. What could she possibly have done?” But as she was under the influence of such an enterprising and patriotic character as Visser ’t Hooft, the many stories she told about her activities in the war become highly plausible.

First and foremost, with the encouragement of the doctor for whom she volunteered, she could dance. Audrey’s celebrity as a dancer for nearly four years at the Schouwburg made her talents valuable to Dr. Visser ’t Hooft and the Resistance for illegal musical performances at various by-invitation-only locations. These events, called the zwarte avonden, or “black evenings,” had first been introduced by musicians as a way to earn money after they had been forced out of the Dutch mainstream by the Kultuurkamer. Soon the zwarte avonden were helping to raise funds in support of those sheltering the tens of thousands of onderduikers hiding across the Netherlands—including those in Velp. They were known as black evenings because windows were blacked out or darkened so the Germans didn’t know of the activities going on inside.

The first documented involvement of the van Heemstras with the zwarte avonden took place on 23 April 1944 when at least one van Heemstra, and likely both Ella and Audrey, attended an illegal performance, their family name listed among those present. From that point on, Audrey wanted to participate.

By this time she, like most Dutch young people, was already suffering symptoms of malnutrition, yet still she danced. “I was quite able to perform and it was some way in which I could make some kind of contribution,” she said.

In another interview Audrey said: “I did indeed give various underground concerts to raise money for the Dutch Resistance movement. I danced at recitals, designing the dances myself. I had a friend who played the piano and my mother made the costumes. They were very amateurish attempts, but nevertheless at the time, when there was very little entertainment, it amused people and gave them an opportunity to get together and spend a pleasant afternoon listening to music and seeing my humble attempts. The recitals were given in houses with windows and doors closed, and no one knew they were going on. Afterwards, money was collected and given to the Dutch Underground.”

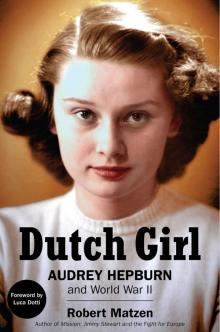

Dutch Girl

Dutch Girl Fireball

Fireball