- Home

- Robert Matzen

Fireball Page 8

Fireball Read online

Page 8

The reply of Charles Castle was instant and heartfelt:

Dear Jimmy:

I got your picture and I want to thank you. I love to look at you. I love your airoplane. You bet I want to ride with you. Will you show me how you do it? May I sit beside you up there? I love you Jimmy and so does Nellie and James. You know Nellie and James are my little sister and brother. Don’t forget to come soon. Please be careful in this bad weather. I love you Jimmy.

Your friend Charles

After this exchange of letters, every single day that Charles stood in the field, the pilot would wave down to him, goggles over eyes and scarf trailing in the wind. It was glorious!

Finally the day arrived for Charles to meet Jimmy Donnally at the Springfield airport. There, Springfield Postmaster William Conkling escorted the eight year old, and the newspaper noted:

“There came a roar of motor—far away, then closer and closer. ‘It’s Jimmy!’ Charles yelled, as he danced about in his great excitement. Santa Claus in person would never have been afforded such an eager welcome.

“Hope and faith had won. Charles was about to realize a dream, to see the fulfillment of his prayers. He stared as down swooped the great green and silver plane and then up to circle the field. Then down to a swift and graceful landing, and to taxi up to the waiting crowd.

“Firm hands held the excited child. As Jimmy cut off his power the little lad was released and he sped to the plane’s side and into Jimmy’s arms with a wild cry. Later came the ride. Little Charles climbed into the plane with Jimmy. The motor roared and the craft swept down the field, into the wind, and was up and away. Jimmy headed due south to Charles’ home and school.

“A little loving mother wept with joy, meanwhile waving a towel to her son there above her as the plane circled the home. In the field was the father at his task of coaxing a living from the soil for his little brood.

“‘There’s Mother!’ the lad screamed into his idol’s ear. ‘There’s Daddy!’ Over the home and the school Jimmy swung his craft low and in wide circles so that the faces of the beloved mother and father were plain to the excited boy.”

Charles was presented with gold wings by Jimmy and not to be outdone, the boy gave the cardboard wings that adorned his little natty flying suit to his Jimmy. Charles thought Jimmy would be his to keep—to take to school for show and tell and to teach him about flying every day—but as the hero himself said, “The mail must go through.” And so he took off, leaving Charles, the postmaster, and a conclave of press behind.

After a chicken dinner for half the village of Pawnee, with all the fixins and ice cream to boot, Charles was asked for a quote by unusually respectful newspapermen. He said, “It was great! Believe me, my Jimmy knows how to fly a plane—and he showed me all about it.”

In conclusion, wrote the newspaper reporter covering the event, “Following came the secret, but assuredly the promised prophecy that one day Charles and Jimmy will be flying the air lines together.”

One half of the prophecy did come true. Jimmy Donnally did fly the airlines, except that the young airmail pilot who landed that June 1930 day in Springfield, Illinois, for the benefit of the postmaster, the press, and 8-year-old Charles Castle was really a young ex-Army flier named Wayne Clark Williams, then 28 and full of the devil, if one could say that the devil made pilots feel like they could conquer not only the skies but the entirety of the world, including the imaginations of eight-year-old boys. That innocent day when flying was new, Wayne Williams created a memory to last a lifetime for several farmfolk in the dead center of Illinois and crafted a story that would be remembered by newspaper reporters in January 1942 after he piloted Flight 3 for the last time.

10. Calculated Mayhem

Jack Frye became president of TWA in December 1934 at a time when the innovative DC-2 went into service and the company sought ways to fly “over weather.” TWA had just created its first three-stop, 18-hour transcontinental flight, in theory anyway, using the new DC-2, but all manner of delays resulted in nobody actually flying coast to coast in anything approaching 18 hours. Frye and TWA owner Howard Hughes now had a vision and sought effective means to get people from coast to coast with alacrity and in comfort.

Around this same time, Carole Lombard sought a different kind of comfort and leaned on her ex-husband for support after the shooting death of Russ Columbo. She also continued to be seen with friend and lover Robert Riskin. Through production of a romantic dance picture at Paramount called Rumba, Lombard diverted her attention with co-star George Raft. A year earlier they had appeared together in the smoldering, moderately successful dance drama Bolero.

George Raft was a pint-sized, tough-talking New Yorker out of Hell’s Kitchen. He had made his mark as the henchman of murderous gangster “Tony” in the original 1932 version of Scarface and would go on to play variations on this gangster theme for decades. He was seven years Lombard’s senior, with a bad-boy vibe and dark good looks. How could Carole resist? Raft would later say, “I truly loved Carole Lombard,” and he truly did. Carole loved the sex, and his warmth, and his lack of turning every interaction into high drama, as Russ seemed determined to do. When Rumba wrapped, the emotionally spent Lombard asked for a leave of absence from her employers at Paramount to get away from Raft and from the pressures of nonstop six-day weeks. The studio said yes.

During the period following the production of Rumba, Lombard decided to devote herself to pleasure today because there might not be a tomorrow, and here the final touches were added to the personal and professional personality of Carole Lombard. Wounded on the inside, she projected all the more passionately on the outside. She threw herself into redecorating the Hollywood Boulevard house and brought in “Billy” Haines to help. William Haines had been a leading man in the silent era and an early casualty of the transition to motion pictures with sound. Haines was gay, and his effeminate speech patterns brought his orientation to the forefront. Suddenly the roles as boy-next-door hero dried up. He became one of Carole’s causes when she asked him to employ his hobby of interior decoration at her new house. He offered advice, some of which she took and some she didn’t, and she paid him for his services even though he told her he wouldn’t cash the check—and he never did. The notoriety that accompanied her support of a gay actor meant more than cash anyway and helped to launch a 40-year decorating career.

Petey tried to redirect her daughter into new interests. One of Petey’s close friends was Elinor Tennant, the first woman tennis player in the United States to turn pro. The 45-year-old Tennant had become a tennis instructor in L.A. and hung out with Petey—nobody in the gang called Bess by her name anymore; to everyone she was Petey. Tennant and Peters played in the same bridge club and shared practice of the Baha’i religion and a belief in numerology and mysticism. Lombard fell in with this crowd and soon spent her mornings on the tennis court, learning from the best instructor in the game. As with everything she took on, Carole obsessed over tennis hours a day, every day of the week.

During a break on the court, Tennant fretted to Lombard about a star pupil, 20-year-old Alice Marble of the American Wightman Cup team, who had collapsed at Roland Garros stadium in Paris a year earlier and now was wasting away in a tuberculosis sanatorium in Monrovia, east of Pasadena. Tennant said that Marble possessed all the natural talent in the world but, frankly, she was morose and bitter at being diagnosed with TB and wanted to die. Her weight had ballooned to 175, and she had given up any hope.

Wanted to die. Remembering the ordeal of 1925, Carole took pen and paper in hand and sat down to write Alice Marble a letter that read:

Dear Alice,

You don’t know me, but your tennis teacher is also my teacher, and she has told me all about you. It really makes very little difference who I am, but once I thought I had a great career in front of me, just like you thought you had. Then one day I was in a terrible automobile accident. For six months I lay on a hospital bed, just like you are today. Doctors told me I was through,

but then I began to think I had nothing to lose by fighting, so I began to fight. Well—I proved the doctors wrong. I made my career come true, just as you can—if you’ll fight.”

Carole Lombard

Marble said, “I kept the letter in front of me for days, trying to think: How can I fight? How can anyone who is ill fight?”

Alice Marble regained enough strength to move from the sanatorium to the home of Elinor Tennant’s sister in Beverly Hills. She said, “Every time I was ready to give up, I remembered Carole’s letter, [and] my obligation to Miss Tennant. Every day I was a little stronger and closer to my goal. I had to get well.” One day Tennant told Marble they were going to dinner at Lombard’s house on Hollywood Boulevard. There Alice met Carole and also Fritz, Tootie, and Petey, who, according to Marble, “ordered her three children around just as if they were five-year-olds.”

Marble wanted nothing to do with tennis courts, but Lombard cajoled her to at least go and watch Elinor’s lessons with the movie stars. By now, Carole had, inevitably, dubbed Tennant with a nickname: “Teach.” Soon the formal name of Elinor had been dropped and the instructor became simply Teach Tennant, and Alice found herself shagging balls during Lombard’s lessons.

“Carole found a general practitioner,” said Marble. “She told me, ‘This is a marvelous man. I like this man; he treated Petey.’ He said, ‘Miss Marble, I don’t think you ever had tuberculosis. You don’t have scars on your lungs.’”

The doctor believed that Marble had suffered a combination of anemia and pleurisy and that if she could drop 15 to 25 pounds, she might play tennis again. “The day arrived,” said Marble, “and my coach and Carole challenged Louise Macy and me to three games of doubles. I felt so shaky, but loved every minute of it.…”

As with Teach Tennant, everyone in Carole’s universe had a nickname, and Marble became “Allie.” Lombard took an intense interest in everything Allie did, hoping the enthusiasm would be contagious. Reported Marble: “Carole would say, ‘What did you eat today, honey?’ I began to lose weight. I lost 45 pounds and we began to talk about clothes. She sent me to USC and I took a course in costume design. Even though I was 21, I had bad acne from all the medication. She sent me to a dermatologist and she always said, ‘You’ll pay me back, but then when I tried, she’d say, ‘Oh shit, forget about it!’”

Marble fell in with the Peters crowd on Rexford Drive. Carole’s entourage included Fieldsie and two psychics who, said Allie, were “the real thing” and so accurate they could make Marble’s “hair stand on end…. They liked Carole…. She’d have them over for dinner. They never did it for pay; they just did it.”

In 1937 Lombard cheered Marble on as she claimed the California state singles title, and the tournament organizer asked Carole to present the trophy to Allie. Lombard said, “Congratulations, Champ. The next trophy will be for winning the national championship.” Marble did just that, capturing the U.S. Open Women’s Singles title at Forest Lawn. Wimbledon titles followed, including a clean sweep in 1939 in singles, doubles, and mixed doubles. With Alice Marble back on her feet, attempts to repay Lombard for all the sportswear purchased and all the doctors consulted were always met with that same refrain: “Oh shit, forget about it!”

Said Allie, “She was always embarrassed when people wanted to thank her. So whenever I won a championship I’d give her a silver tray. I must have given her 25 over the years.”

On the Hollywood courts Carole met other Tennant protégés, including Bobby Riggs and Don Budge. “I play tennis now two and three hours a day,” said Lombard. “I’m working harder at it than I have ever worked at anything.”

But the sponsorship with Marble went deeper as Lombard sent the tennis star to Paramount for drama and dancing lessons. Allie went along with the idea but knew she didn’t have the natural talent to take it anywhere. One thing she could do, and loved to do, was belt out a song in a voice much like Kate Smith’s. It was with ambivalence that Marble saw Lombard take over her life, and within the entourage, discord bubbled.

“Teach was a funny person,” said Marble. “She loved Carole, but hated anything that took me away from tennis. I was the closest thing to a daughter she ever had [but] Carole was very persuasive.”

Lombard had found her way past the death of Russ Columbo and all its conflicts and mysteries. A mystic from India who visited Hollywood, Swami Daru Yoganu, took one look at Carole Lombard and “the emanation of her Karma, or life force,” and labeled her “an old soul” whose life force went back 900 or 1,000 years. It would be all too easy to dismiss such a story as the work of Paramount’s publicity department—except to those who knew Carole and experienced the breadth of that soul, her easy manner and generosity of spirit all packed inside a woman just 25 years of age.

She was always in motion, always doing something, always devoted to a cause or sweating on a tennis court or investigating ways to buy publicity to further her career. In the Hollywood of 1934, elaborate parties were all the rage, and Lombard reconceptualized that entire fad by planning and hosting parties. Not just cocktail parties for the Hollywood elite, but a series of lavish, raucous theme parties at the Hollywood Boulevard house that included the hillbilly party, with a complete barnyard motif that included live cows and flailing chickens, and the hospital party, with waiters dressed as doctors and supper served on operating tables, and yes, in bedpans. Unfortunately, the hospital party flopped because guests in formal attire refused to change into hospital gowns, leaving the hostess with egg on her face. Her biographer, Larry Swindell, said that Lombard admitted becoming “a madcap party-giver with rank calculation, courting the kind of publicity that would identify her, personality-wise, with the roles she wanted to play.”

Lombard made no apologies for being a performer at heart. “What a ham,” exclaimed Alice Marble. “What a ham!” So the professional personality suited her natural energy level and gregarious nature. Of course, all Hollywood knew what Lombard was up to, and many bought in while others resented the power grab and the press’s subservience to the overt manipulations of a marginal star.

She capped a year of these parties by renting the entire Venice Amusement Pier at Oceanside Park for an evening and inviting most of Hollywood to come have fun at her expense. She staged the party in honor of real estate developer Alfred Cleveland Blumenthal. The Paramount Pictures crowd dominated, including Marlene Dietrich, Claudette Colbert, Randolph Scott, and Cary Grant, but Hollywood A-listers Richard Barthelmess and Clive Brook were there, along with Josephine Hutchinson, Toby Wing, Constance Talmadge, Warner Baxter, Regis Toomey, and Louella Parsons. French actress Lili Damita showed up as well without really knowing or caring what an amusement park was. She wanted to be seen, and so she dressed to the nines and brought in tow a young Aussie unknown named Errol Flynn, wide-eyed and fresh off the boat from England.

The Venice Pier party would mark Lombard’s swan song in over-the-top entertainment and end a half year away from soundstages. Her return to Paramount Pictures would be supervised by Ernst Lubitsch, the new general production manager at the financially troubled studio. The German-born writer-producer-director was already known for “the Lubitsch Touch,” his particular talent for crafting elegant, bewitching scenarios. It was no secret that Ernst Lubitsch had become a Lombard fan. After reviewing her performances in Twentieth Century and Lady By Choice—both of which had been made away from Paramount—Lubitsch wanted to give direction to Lombard’s career by capitalizing on her Sennett-schooled affinity for comedy because, frankly, she could open a roadside stand selling eggs, she had laid so many in melodrama. Carole had earned the unflattering nickname of the “Orchid Lady” after an earlier melodrama called No More Orchids and a subsequent string of melodramatic performances in clinkers. Hence the party campaign of 1934–35 and its focus on the kind of surrealist themes found in Twentieth Century. Reviewers suddenly treated her like a shiny new star, and the brain trust—Carole, Fieldsie, and Myron Selznick—believed this comedy thing could become so

mething uniquely Lombardian.

The script chosen now by Paramount boss Lubitsch for Lombard was Hands Across the Table, about a manicurist dreaming of marrying a rich husband but falling for a young playboy whose family had been wiped out by the Depression. The story had been purchased for Claudette Colbert, the star of two 1934 blockbusters, DeMille’s Cleopatra and director Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night. Claudette didn’t need a hit. Carole did, so the self-assured Lubitsch ordered the Hands Across the Table script rewritten for Lombard, then assigned Mitchell Leisen, former assistant of Cecil B. DeMille, to direct and dashing newcomer Fred MacMurray to co-star with Lombard.

Carole found herself in the right place at the right time as a new genre, the screwball comedy, took hold with It Happened One Night, which had earned Oscars for Colbert, for her male lead Clark Gable, and for director Capra and the picture itself.

Suddenly everybody wanted to see comedy with a surrealist touch, and Hands Across the Table stood at the forefront. Lombard’s popularity spiked. But Carole, or possibly Fieldsie, or possibly Myron Selznick, realized the impact on Hollywood of the recently enforced Motion Picture Production Code, a set of rules governing morality in movies. This set of edicts fell upon the studios like a nun’s habit in response to the sex and violence in Depression-era pictures. Main catalysts for change were two overtly sexual actresses: Jean Harlow and Mae West. Now with pejorative rules in place, Lombard tested the edicts to attract attention and build her brand. She seized every press opportunity, showing as much leg in publicity shots as decency allowed. She went braless in the slinkiest costumes that could be designed and worn onscreen, iced her nipples before cameras rolled, and jiggled when possible. She did whatever she could to ascend to the role of sex symbol. Just because she had veered into comedy didn’t mean she wanted to stop being sexy because, as everyone knew: Sex sells.

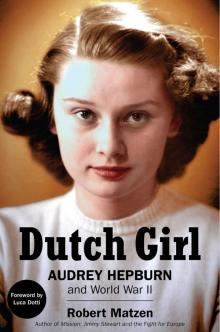

Dutch Girl

Dutch Girl Fireball

Fireball